Mustafa Quraishi

“ The working class of our country has been made to stand in line, begging for food. If this lockdown goes on for long, we will actually have a huge population standing in line for food.”

New Delhi based photojournalist, Mustafa Quraishi could have easily chosen to continue shooting and documenting the plight of the people during the pandemic but instead he chose to leave his camera at home and provide relief to those who were abandoned by the State.

“I had a press pass and I wanted to do more than just my job as a journalist. I didn’t see a point in clicking pictures anyway. The plight of the poor was not hidden from anyone. They were on the road walking. They were outside our houses, hungry and stranded at construction sites. All we had to do was look outside our houses. What was the point of these pictures, if most people weren’t even moved by what they saw with their own eyes.”

In the early days of the lockdown itself, Mustafa started volunteering with the Civil Defence and the police, as well as a citizen run initiative called the ‘Gurgaon Nagrik Ekta Manch’ in Haryana. He drove around in his own vehicle, sometimes doing 120-150 kms a day carrying upto 2,000 cooked food packets and 70-80 dry ration kits.

“ Giving a 4 hour notice for the lockdown was ridiculous. They should have let the migrants leave first.”

Critical of the government and the bureaucracy’s role in managing the lockdown, Mustafa shares how not only did the government fail to provide adequate relief but also made things harder for the civil society volunteers. “Many community kitchens were out of cartons for food distribution. Instead of helping us with cartons, they just handed us a manufacturer’s number. The entitlement form that the poor needed to fill up to get the rations, was being sold for Rs 100. Then let’s come to the masks...The government was insisting that everyone must wear masks for protection but how can a poor person afford a Rs 10 mask? We asked the government to arrange for cloth masks and even that request was not fulfilled. I had to ask a leading fashion designer to help us with masks. Many migrant workers didn’t have access to clean water. The least the government could do was provide water tankers in their communities but even that basic need for water was overlooked. During the lockdown, I had to travel to Delhi twice and both times I was fined for speeding on empty roads. They started charging us a toll at Manesar, the fuel prices were increased. It was as if they had decided that we won’t work and won’t let others do any work either. But thankfully, Haryana Police were very supportive of our work. Without them food distribution could not have happened.”

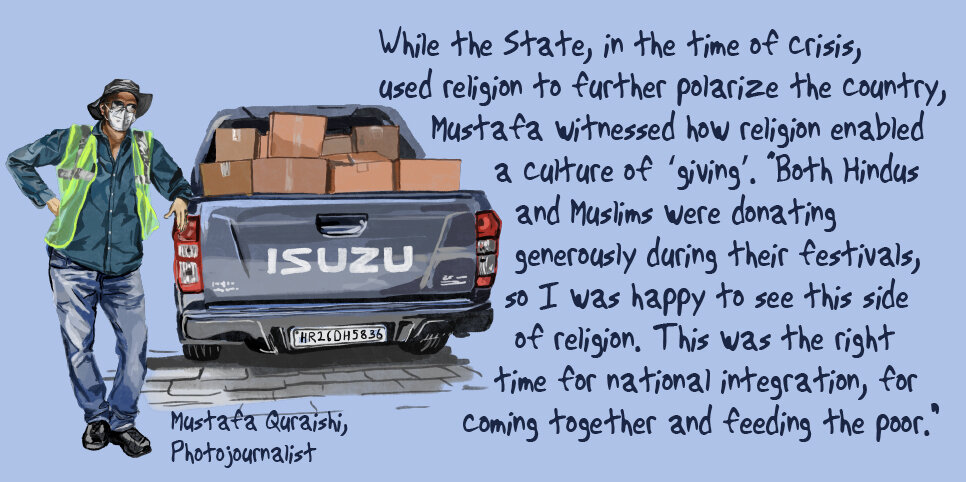

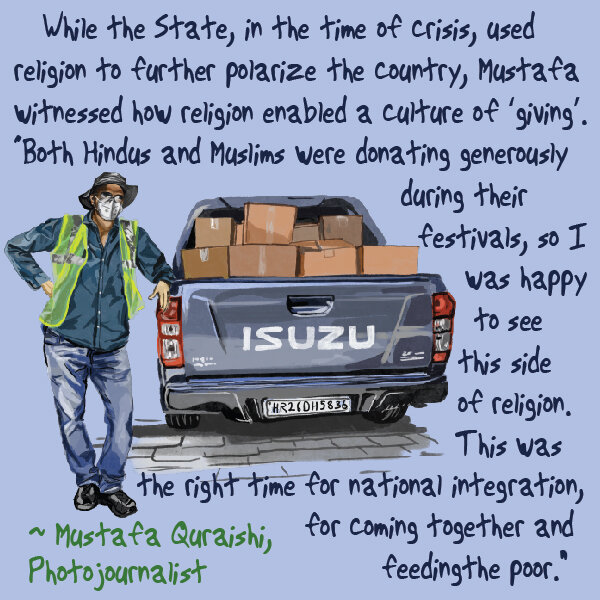

While the State, in the time of crisis, used religion to further polarise the country, Mustafa witnessed how religion enabled a culture of ‘giving’.

“Both Hindus and Muslims were donating generously during their festivals, so I was happy to see this side of religion. This was the right time for national integration, for coming together and feeding the poor.”

As a photojournalist, I have covered so much trauma, seen so much poverty and distress but small incidents still affect me. For e.g, One day someone told me – ‘Bhai, iftar karne ke liye kuch khana nahi hai to roza rakhne ka kya fayda (I have no food to break my fast, so what’s the point in fasting in the first place)?’ In these moments, I feel grateful that I am doing something constructive right now.”

In the midst of this crisis, people who risked their lives to volunteer have been Mustafa’s support system and continue to inspire him. “A young couple who left their kids at their parent’s place to work for the community, some residential welfare societies and some corporates like Hero MotorCorp… had they not existed, there would have been no hope for the country.”

Interviewed and Edited by Pooja Dhingra

Illustrated by Anushree Agarwal