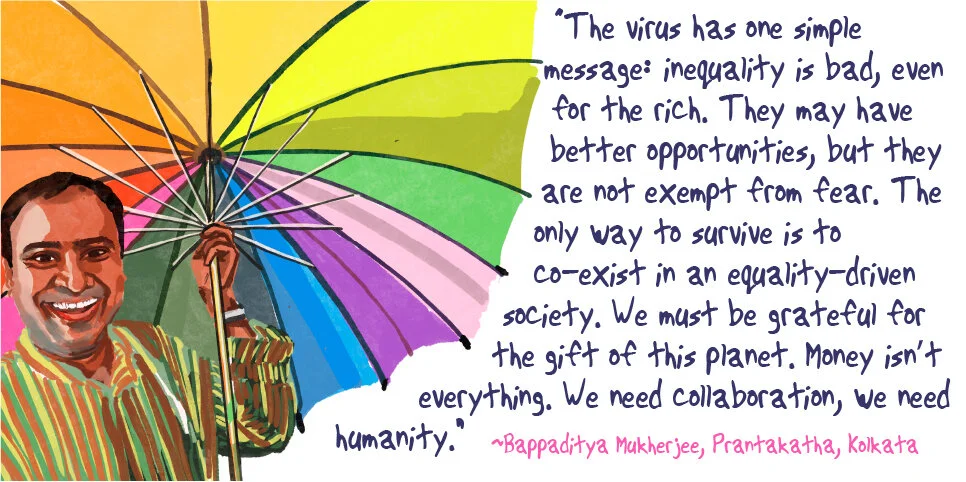

Bappaditya Mukherjee

A defector of the mainstream, a shining light.

Bappaditya is a true Renaissance man.

After coming out of the closet in a pre-Internet era, comprehension of his sexual identity became a challenge, without the now-available tools of representation in media and open conversations. It took simply a minute, the simple act of coming out and being honest about himself, for the mainstream to reject him, and for his friends to shun him. In the 90s, the most relevant part of his social being became his sexual orientation; and despite hailing from an upper-class family, he was immediately marginalised.

Soon, Bappaditya started to meet people who shared their stories of pain and marginalisation with him. Despite conversations around LGBTQUI being rare then, he was motivated to create a space for youth from various cross sections of society like himself to engage in healing conversations, to transform their pain into strengths. While the people may still be marginalised, the storytelling itself would be of hope, friendship and empowerment.

Prantakatha (translated from Bengali to mean ‘the narrative from the margins’) was started in 2006. Since then, it has worked as a network, birthing various hub-organizations who work on issues like child trafficking in bordering areas to Bangladesh to LGBTQUI rights to the rights of Muslim women. Now, Prantakatha is a space where young people learn from their pain instead of avoiding it.

When reflecting on the challenges for women & the LGBTQUI community during the pandemic, he states, “The pandemic deprived women and the queer community of their living spaces. Their homes are breeding grounds of violence, and the communities are always in search of safe spaces for socialisation. The lockdown was implemented from a patriarchal, heteronormative and industralised lens. It was decided upon by the central unit, without the states being able to make any decisions. This created havoc in so many different sections of the population.”

“I have heard too many horror stories of abuse my people have faced during the lockdown. There are so many cases of trans men, currently in transition, who were forced into marriages or raped. Kolkata barely has any trans shelter homes. This is because policies and policy makers are yet to understand multiplicity of challenges of gender and sexuality minorities. All institutional health support was rapidly taken away. Trans people taking hormone replacement therapy lost access to their medicines, and faced severe challenges. This is pure violence, and it hits deep. Since the lockdown was announced in March, we at Prantakatha have received multiple cases of death by suicide, every month. All from the LGBTQUI community.”

When discussing the groundwork happening during the pandemic, Bappaditya speaks of hope.

“Ah, the collaborations. The solidarity!” Bappaditya smiles. “During the challenges, the positivity has been overflowing. I have seen young queer individuals creating awareness of, and access to, suicide helpline numbers on social media. I have seen the trans community raising dry ration and food for themselves and others. The challenges have helped create leaders. What was initial hesitation rolled into collective action.”

He shares a beautiful story of mutual aid and solidarity.

“I go for my morning walks in a park in South Kolkata. I would see a group of 35 elderly women who would ask walkers and passers-by for donations. We quickly formed a relationship, and I learnt they had been thrown out of their homes. I took to Facebook, and keeping in mind how people donate easier to structures of worship than to those in need, I posted, asking my audience why they were trying to be blessed by the Mother Goddess, when our grandmothers needed our help. A group of young people got together, and we decided to help out as much as possible. Luckily we were able to actively help the women before the pandemic struck, so now Prantakatha has access to their medical histories, and we were able to provide them with quality care. Just before the lockdown was declared, we arranged rented accommodation for them, and provided them with food material and dry rations. The women were extremely happy, as were we. Additionally, we provided accommodation and food to groups of migrant children.”

In addition to the pandemic, West Bengal and neighbouring states had to face Cyclone Amphan. Prantakatha responded immediately to the shelter and food crisis, and transferred money from a Covid-19 relief fund to support over 5000 families with food. With the help of Goonj, Prantakatha started a rainbow kitchen, aimed at feeding the queer community until the end of the year. Food from the rainbow kitchen is being delivered across Bengal.

Prantakatha tirelessly met the various challenges of the pandemic with decentralised collaborations. Realising the importance of working within the system, the organisation collaborated with the Women’s Commission, the Child Protection Commission, the Kolkata Police and the Municipal Corporation. With all the stakeholders functioning in a decentralised manner, they were able to expand their reach beyond regular bounds and help people with their problems. The organisation also received a lot of assistance from MPs and MLAs with cases about people being thrown out of their homes.

“Communities in Kolkata are more likely to accept women in leadership positions,” states Bappaditya. “The balance women are able to create and embody when approaching the police or the media is wonderful to witness. Communities truly rally behind powerful women, and enable them to succeed.”

He relates a beautiful tale of hope about Sandeep, a young, gay man who has survived a severe traumatic experience. Instead of choosing the desolate alternative, he took it upon himself to create a system for the future, to bridge the two populations of the police and the LGBTQUI community using the weapons of sensitisation and education.

When discussing the possibilities in the post-pandemic world, Bappaditya says, firmly, “The virus has one simple message: inequality is bad, even for the rich. They may have better opportunities, but they are not exempt from fear. The only way to survive is to co-exist in an equality-driven society. We must be grateful for the gift of this planet. Money isn’t everything. We need collaboration, we need humanity.”

“I strongly believe that compassion is the result of us understanding our vulnerabilities and limitations. People must understand that compassion isn’t a product of living a luxurious life, but it is our human existence which makes us compassionate. Without it, there is no life, no survival of our species. Compassion does not necessarily come out of any spiritual understanding; rather it is grounded more in the practical experience of facing challenges, head-on and within community,” finishes Bappaditya, with a smile.

Interviewed by Nida Ansari

Edited by Shayontoni Ghosh

Illustrated by Anushree Agarwal